Most recently updated January 18th, 2022

Estimated Reading Time: 25 minutes

Earlier this year, after months of COVID lockdowns and weeks of gloomy rainy local weather, I couldn’t stand it anymore!!

All of my local trails had become rivers of mud, and greenways just don’t feed the soul like sunshine and a soft forest path.

Besides, walking greenways too much can also hurt your joints….

So I abandoned my spot on the Ark, and took off on a solo roadtrip down the East coast.

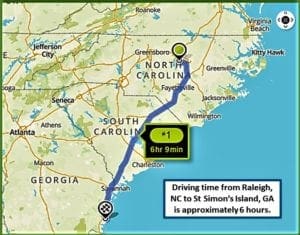

Starting from the Raleigh area, I drove all the way to St Augustine, FL (which is a story for another time) and then worked my way back up the Coast towards home.

My first stop on the way back up was St Simon’s Island, Georgia 🙂

St. Simons, the largest barrier island in the Golden Isles, lies just off the Georgia coast.

It’s a favorite family beach destination for visitor’s in the summertime.

Off the beach, St. Simons Island is dotted with remnants of historic sites you can visit, like the St Simon’s Lighthouse, Fort Frederica National Monument, and Christ Church.

You can also follow the ancient footsteps of the very first tourists to the island, who travelled either by walking the forest paths or paddling down the waterways.

I did some research and found a historic hiking spot at Cannons Point Preserve on the north end of the Island.

Among other reasons to visit, the trail at Cannon’s Point Preserve leads you to some extraordinary abandoned historic ruins along the coast.

Some of my posts contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through an affiliate link, I will receive a small payment at no additional cost to you. As an Amazon Associate, and other marketing affiliations, I earn from qualifying purchases. See full Disclosure page here.

Cannon’s Point Preserve

Cannon’s Point Preserve (CPP) is a unique 600-acre primitive greenspace at the north end of St. Simons Island.

The peninsula has over six miles of salt marsh, tidal creek and river shore line that provide habitat for oysters, birds, fish, manatee and other wildlife.

Cannon’s Point Preserve also contains some of the last intact maritime forest on St. Simons Island.

The property was acquired by the St. Simons Land Trust in September 2012, with the generous support of Sea Island Acquisition and many other community members.

In addition to being open for public recreation, CPP puts effort into research and environmental protection projects.

One of those projects is the Living Shoreline.

Living Shoreline

Several years ago, the St Simons Land Trust installed a demonstration Living Shoreline project to restore the eroding bank of Lawrence Creek at the former site of Taylor’s Fish Camp.

The basic idea is to employ natural structure and processes to stabilize and enhance the habitat.

The Living Shoreline process uses native plants and consolidated oyster shell, which will eventually become a natural habitat for intertidal plants and animals.

Most of the 8,000 bags of oyster shells used for the Living Shoreline project were purchased and trucked in from North Carolina, but some shells came from Cannon’s Point Preserve (CPP) itself.

Throughout the work, oyster shells from the Preserve’s pre-historic Native American middens were collected, cleaned and weighed.

These shells were documented, then returned “home” to nearby tidal waters to become part of the bank stabilization and restoration.

St. Simons Island History

WARNING: I’m about to go full History Geek for a while, so if you’re only interested in visitor information, please use the links in the Menu to skip to that part 🙂

The first inhabitants of St. Simons lived there during fishing season about 2,000 BCE (Before the Common Era). No one knows what they called themselves.

St. Simon’s Park

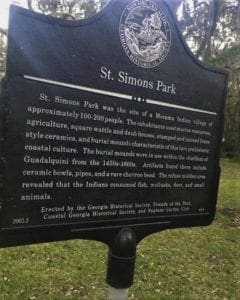

St. Simon’s Park

Thousands of years ago, just north of the village on St. Simons Island, there was a thriving community of about 200 people from the area’s earliest indigenous tribe.

Today, on the southern edge of St Simons Park, along a narrow lane, is a low earthen mound.

Growing upon it are majestic oak trees that serve as a natural monument for the more than 30 Indians buried in the mound.

These early Native Americans travelled seasonally each year to enjoy the area’s game and shellfish.

Today, visible remains of shell rings, both on the mainland and the islands, attest to those early visits.

Shell Rings – More Than a Trash Heap

Located along the barrier islands and coasts of Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida, shell rings (also called middens) are circular deposits of shell, bone, soil, and artifacts.

Speculation is that these rings were used for ceremonial purposes as well as a place to put discarded shells and other trash.

Native Americans created these features during the latter part of the Late Archaic Period (4,200 to 3,000 years ago).

A much later local historic tribe, which encountered the Europeans, became known as the Timucuan.

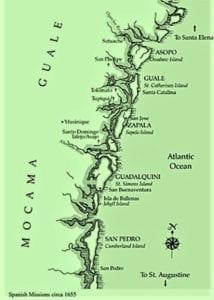

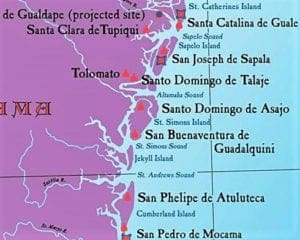

Mocama and Guale Province

The eastern Timucuan were a loose organization of seven tribes that spoke at least five different dialects of the Timucuan language.

St. Simons Island was the northern boundary of the tribal province of Mocama that extended southward to the St. Johns River.

The town of Guadalquini was located on the south end of the island (at the site of the present day lighthouse) and the town’s name also applied to the island itself.

Just above Mocama was the territory of the Guale people, occupying the coastal fringe between the Altamaha and Ogeechee Rivers.

First indigenous contact with Europeans on Georgia’s coast may have come as early as 1564, when the Guales encountered soldiers at Fort Caroline, a French Huguenot outpost on St Catherine’s Island.

Spanish Florida

In the 1570s, the coastal area stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico – known as the Debatable Land – saw the arrival of hooded Franciscans and Dominicans, who built missions hoping to convert their native hosts.

By the mid-16th century, Spain had come into her own as the most powerful nation on earth and had thoroughly staked out her claim in the New World.

Any French designs on occupation along the Atlantic coast had been quickly squashed by the land-hungry Spanish:

-

-

- Ponce de Leon claimed the southern region for Spain in 1513, and

- Hernando de Soto probed western Georgia in 1540.

-

During the 17th century, St. Simons Island was one of the most important settlements of the Mocama missionary province of Spanish Florida.

The Mocama and Spanish missionary cultures co-existed for some time, but forced indoctrination and Spanish meddling in Tribal customs led to the first native uprising in 1597, which left at least five priests slain along the Coastal settlements.

There followed a bloody period of war between the tribes and Spanish, which ultimately resulted in the Spanish missionary “victory” of sorts, and from 1606-1655 the Spanish missionary effort reflected a steady growth.

Now Spain had a total of ten Mocama and Guale missions – and Guadalquini on St. Simons was one of them.

But a series of events from 1663 – 1683, including expanding English settlements and more Indian attacks, increased the confusion and helplessness of the missionary Indians.

Finally, in 1684, Guadalquini was ransacked and burned by pirates, and St. Simons Island was abandoned forever by the Timucuans.

So, after almost 125 years under Spanish dominion, the Mocama and Guale Indians were no more.

So, after almost 125 years under Spanish dominion, the Mocama and Guale Indians were no more.

Their land would now be known as “Georgia”.

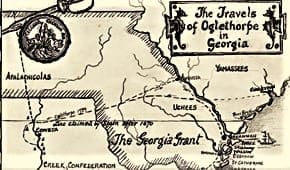

The Georgia Colony

Though the Mocama and Guale were gone, the Spanish persisted.

By the early 1700’s, Georgia was the epicenter of a centuries-old conflict between Spain and Britain.

The Georgia Colony was initially conceived as a philanthropic effort to give refuge and a fresh start to London’s indebted prisoners.

But by the time it was established in 1732, Georgia’s primary function was to protect South Carolina and other southern colonies from further Spanish invasions coming through Florida.

James Edward Oglethorpe, a philanthropist and an English general, along with twenty-one other men, formed a Trust and created a charter to settle a new colony.

With his background and abilities, his relative youth – he was only 35 – his independent wealth and his lack of attachments, Oglethorpe was well suited to found a colony.

They named it “Georgia” in honor of the English King George II.

Settling Savannah

The Trust set up the most rigid screening process for prospective colonists of any American colony.

Not all applicants were accepted, and a debtor needed permission from his creditors to join the expedition.

Each settler was given free passage, tools, agricultural implements and seeds, along with 50 acres of land.

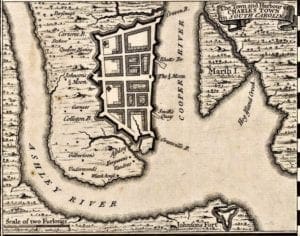

The first Georgians arrived off Charleston in January 1733.

Two weeks later, the colonists settled in four large tents on a bluff overlooking the Savannah River, 12 miles inland from the sea.

Oglethorpe laid out the town and named Savannah’s principal streets and squares for prominent Carolinian settlers who had donated livestock and funds for the “buffer” colony.

To prevent friction with the nearby Creek tribes, Oglethorpe sought permission to settle from Tomachichi, the aging chief of the Yamacraw Indians, who lived on the bluff.

With the help of Mary Musgrove, a mixed-race interpreter, he and Tomachichi signed a treaty giving Oglethorpe access to all land between the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers as far up as the tide ebbed and flowed.

The islands of Ossabaw, St. Catherines and Sapelo, along with the small tracts above the bluff were reserved for the Creek to camp.

Good Publicity

In 1734, Oglethorpe, with a good eye for public relations, returned to England accompanied by Tomachichi, his wife, nephew and five Creek chiefs.

London was amazed, and Oglethorpe was received as a national hero.

Parliament granted Oglethorpe £26,000 for the colony’s defense, which helped him to recruit 130 Scots Highlanders and their families, who sailed to the new colonies in 1735.

The Scots settled on the Altamaha River at a site previously selected by Oglethorpe near old Fort King George.

Oglethorpe followed a few months later, arriving in Savannah with another 230 colonists who were destined to settle on St. Simons Island.

Fort Frederica National Monument

Oglethorpe led his newest settlers in small boats through the inland passage from Savannah to St. Simons, arriving February 18, 1736 – a full four years after the founding of the Georgia colony!

They made good time, because Oglethorpe kept the beer supply in the first boat to prevent straggling 🙂

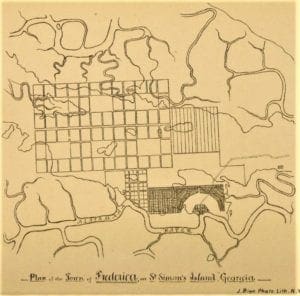

By mid-March, 44 men and 72 women and children were in the new settlement, which had been named “Frederica,” after the Prince of Wales.

When Oglethorpe brought the weary travelers ashore on St. Simons Island, he immediately marked off the streets of Frederica and erected shelters.

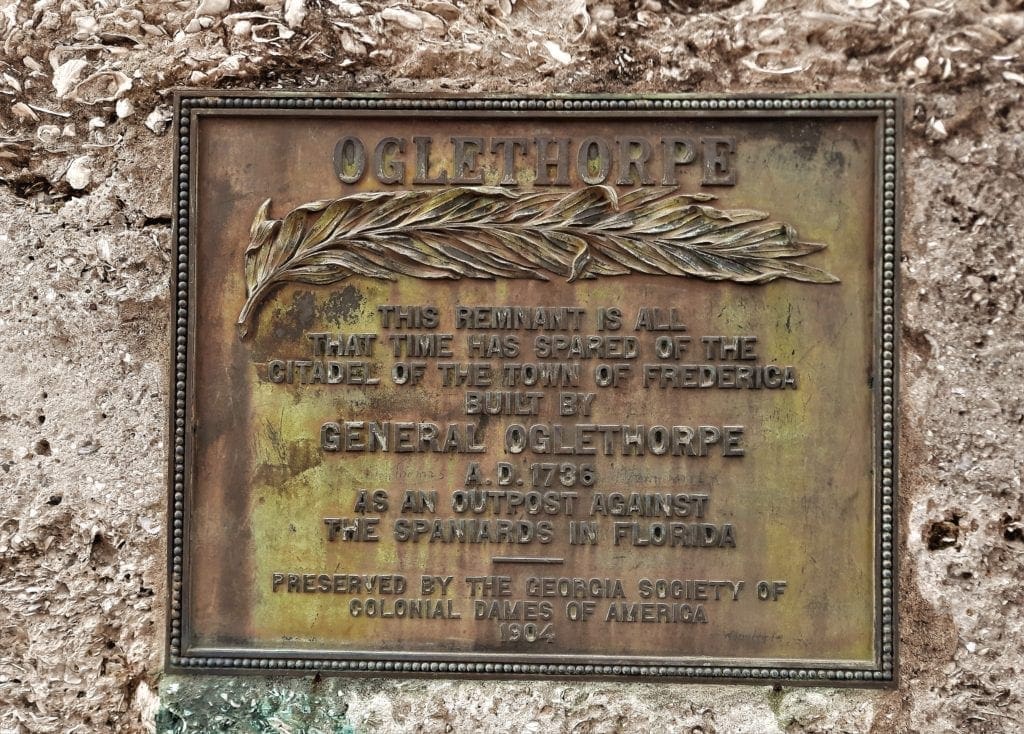

And then – because the Spanish were enraged at this latest English intrusion – Oglethorpe began the construction of Fort Frederica to protect Georgia’s southern boundary.

Fort Frederica – A Planned City

Oglethorpe made his permanent headquarters in Frederica rather than in Savannah.

The town site was set strategically on a bluff overlooking a U-shaped bend in the river, using an abandoned 35-acre Indian field, which eliminated the need to clear timber.

The town was laid out with lots divided into two wards by a wide avenue eventually known as “Broad Street.”

This main thoroughfare was lined with orange trees, and most of the lots were occupied by small clapboard houses or log huts.

Each freeholder was given a 60’x90′ plot on the high street for their house and garden; those which fronted the river had smaller 30’x60′ plots.

In addition to the town lot, each settler had a garden lot on the outskirts of town, with the balance of his fifty-acre grant farther out.

To the east of town was a large meadow used for grazing cattle.

Orchards provided dates, limes, figs, peaches and pomegranates; cotton was grown in small quantities, and hay was cut and stacked in the meadow.

In those early days, the mainstay of the town was the fort.

Encompassing almost an acre, the fort boasted a blacksmith shop, a well and two brick and timber storehouses of three floors each, with the top floor of the east storehouse used as the town’s chapel.

The Fort’s first walls were surrounded by a six-foot moat. An earthen spur jutted out into the river, and cannon were placed at water level.

Initially, the fort’s defense rested upon the settlers.

Military training was a part of each day; firearms were kept at the ready, and discipline was strict.

Later that year, in the summer of 1736, the Spanish sent Antonio de Arredondo to meet with Oglethorpe and deal with the English threat.

After much discussion, the men both finally agreed to withdraw from the questioned area below Savannah.

But apparently Oglethorpe didn’t really mean it. 😉 He knew that he could strengthen the area before the Spanish could react.

Oglethorpe immediately detailed four more forts to be built:

-

- Lt. Mackay and his Highlanders began construction on Fort St. Andrews at the northern end of Cumberland Island.

- Fort William was constructed on Cumberland’s southern end, (the inlet between there and Amelia islands was guarded by a small “scout station” until 1740, when the fort was complete)

- Fort St. George was placed at the mouth of the St. Johns River – just above St. Augustine

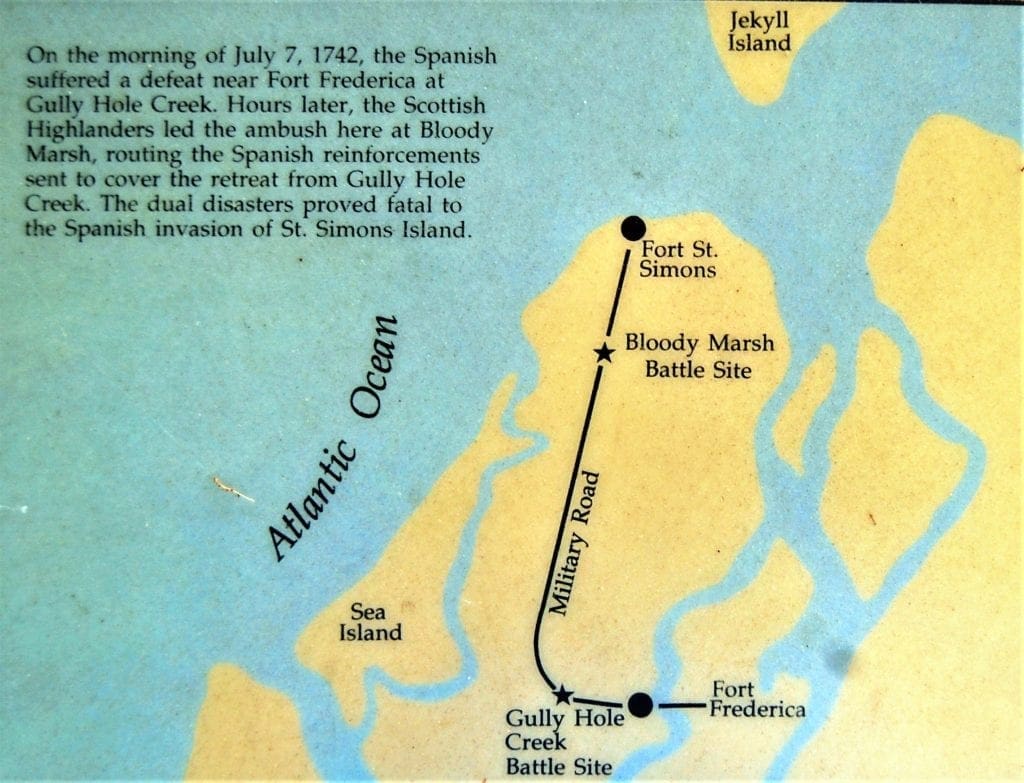

- and an additional fort, Fort St Simons, was placed on the St Simon’s southern tip, at the site of the current lighthouse.

Oglethorpe now had a string of outposts, in addition to Frederica, that would keep watch for any Spanish activity in the inland passage.

The fortifications were money well-spent, as the coastal war between Spain and Britain intensified again in 1739, when England declared war on Spain (the War of Jenkins’ Ear).

The next few years saw many land and sea battles along the Coast, all the way South to St Augustine.

The Georgia Colony’s future was finally decided in July, 1742 when the Spanish were routed by British and Scottish soldiers on St. Simons Island.

The Battle of Bloody Marsh

After a first victory at Gully Hole Creek, Fort Frederica’s troops soundly defeated the much larger Spanish force again that same day in the Battle of Bloody Marsh, ensuring Georgia’s future as a British colony.

The War of Jenkins’ Ear would finally be settled on the battlefields of Europe, and within two decades Spain would leave Florida entirely.

However, for Frederica, the victory was bittersweet.

Following the decisive victory, Oglethorpe left Georgia and returned triumphantly to England, to begin the second half of his life as a country gentleman and member of Parliament.

Five years later, in 1749, the declining military threat to the Georgia coast saw Fort Frederica’s regiment disbanded. Of some 600 soldiers, most returned to England.

In 1751, the contents of the Frederica public storehouse were sold in Savannah, and the town was virtually deserted.

The Trustees awarded 106 individuals ~ 75,000 acres of land in the last year of the Trust. And then, unable to extract further monies from Parliament, the Trust gave up its charter in 1752, a year before it expired.

After Frederica Was Abandoned…

-

- In 1758 a fire destroyed most of the structures in the town.

- The remainder were pillaged and burnt in the 1778 occupation of “Brown’s Rangers” during the American Revolution.

- Land owners on the island used Frederica’s rubble to construct new buildings during the Plantation Era (1758-1860).

- Then Captain Charles Stevens began purchasing land in the old fort and town, and the Stevens, Dodge and Taylor families created small farmsteads throughout the area.

- In 1903, Mrs. Belle Stevens-Taylor donated “the old fort and sixty feet in all direction” to the Georgia Society of Colonial Dames.

Finally, in 1941, the Fort Frederica Association was formed to purchase the remaining land to give to the National Park Service.

How You Can Visit

Today, the archeological remnants of Frederica are protected by the National Park Service.

Today, the archeological remnants of Frederica are protected by the National Park Service.

The site is open daily 9:00 am – 5:00 pm (closed most holidays).

There is no fee to enter the park.

Address: 6515 Frederica Rd, St Simons Island, GA 31522

Ranger-led tours and soldier/colonial life programs throughout the year recall life in Georgia’s second town.

The park visitor center features exhibits and an orientation film, which is shown every 30 minutes.

Christ Church

Christ Church, also located on the north end of the island, is one of the oldest churches in Georgia, with worship services held continuously since 1736.

But though Frederica and Savannah were consistent in a location for their worship, they had a hard time finding a long-term spiritual leader.

Wesley Brothers

The first, and probably the most famous, to attempt a ministry in the Georgia Colony were John and Charles Wesley, who came to Georgia with Oglethorpe in 1736.

They had been tutors at Oxford and eagerly embraced the opportunity to convert the “heathen Indian” in the New World.

John, the elder brother, became minister to Savannah, while Charles was Oglethorpe’s secretary, minister at Frederica and Secretary of Indian Affairs.

Despite their good intentions, these young men, ordained by the Church of England, were totally unsuited to the realities of the Georgia frontier ministry.

Charles’ constant criticisms of Frederica irritated the settlers and Oglethorpe alike.

Beata Hawkins and Anne Welch, a pair of sharp-tongued gossips, spread malicious rumors about him, until the laundry woman even refused to wash his linen.

Charles returned to England after only three months in Georgia, with his congregation “reduced to two Presbyterians and a Baptist.”

John visited Frederica for about a month in May of 1736, just after Charles left. He returned again in July for about three months, left and finally stayed almost three weeks again in January.

Despite his efforts, John found no better luck than his brother in winning the confidence of the Frederica folk. (Beata Hawkins threatened to shoot him!) So John confined his ministries to Savannah.

But the young minister incurred the wrath of the townsfolk there as well, and was forced to slip away in the dead of night, and catch a ship to England to avoid arrest.

Though considered a founding cleric, he was only in the Georgia Colony from February 6, 1736 until December 2, 1737.

Eventually John Wesley made his name by founding the Methodist Church in England.

For 30 years after the Wesley brothers’ departure, the Colony saw a flurry of short-term ministers. But despite the early minister merry-go-round, by 1807 it was decided that population in the area warranted a permanent place of worship.

So, in 1808 the State of Georgia gave 100 acres of land on St. Simons to be used for a church and its support.

Called Christ Church, Frederica, the structure was finished in 1820.

The parish in St Simon’s would be one of the first to form the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia in 1823 – along with Christ Church in Savannah, and Saint Paul’s Church in Augusta.

During the Civil War, invading Union troops commandeered the small building to stable horses and partially destroyed it.

In 1884, the Reverend Anson Phelps Dodge, Jr., built the present structure in memory of his wife, Ellen. (This historic building is still in use today.)

The grounds contain a cemetery with graves of early settlers and many famous Georgians; the cemetery’s oldest tombstone is from 1803.

You can also walk a garden path with a memorial to the Wesley brothers.

How You Can Visit

Address:

6329 Frederica Rd, St Simons Island, GA 31522

Hours:

Christ Church, Frederica is open to the public for tours Tuesday through Sunday from 2:00pm – 5:00pm. (Closed on Easter and Christmas)

Visitors can walk the grounds for free.

Services:

Services are held daily at 5:00pm, on Fridays at 11:30am, and every Sunday from 8:00am – 11:00am.

Hike Cannon’s Point

Okay, I have now left Historyville – or have I? 😉 Let’s talk about hiking at Cannon’s Point Preserve!

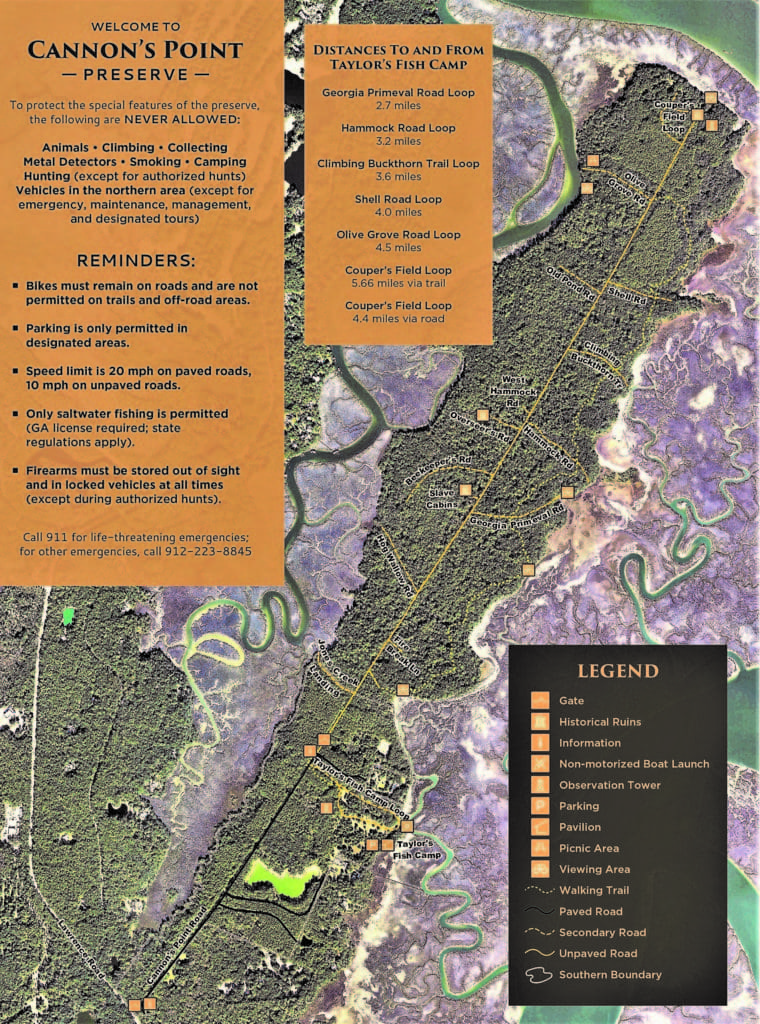

To get to the trailhead at Cannon’s Point, turn down Lawrence drive and go all the way to Taylor’s Fish Camp.

You can park, sign the guest book, and make use of the only toilet facilities at the Preserve before you hit the trail.

I had researched the trails before heading over, so I already knew that I wanted to hike down to the Couper Plantation ruins at the Point.

There are basically 2 routes you can take from the Fish Camp to the Couper ruins: the marsh trail or the dirt road.

When we visited in February, the whole region had literally been under a raincloud for months – in fact, it rained the day before our hike – and the marsh trail was pretty wet.

So we decided to hike the road.

The Trail

The hike or bike ride to the plantation house ruins (Coupers Field Loop) is roughly 5 miles round trip.

I had invited That Man to join me in St Simon’s, so he was hiking with me.

That was fun for us, but the trail is not at all difficult or dangerous, so it would be fine to hike it alone.

It’s also perfectly suitable for children – but be prepared to carry them: the road surface is rutted dirt and grass and isn’t very good for strollers.

A dirt bike would work, though.

They say this trail takes people an average of 2 hours of hiking or 40 minutes of biking.

Our goal was to have the plantation ruins be our turn-around point, but we went down many of the side-trails along the way, which added time and mileage – I think we ended up going around 8 miles total.

Exhibits and historic ruins along the way took us backwards in time from the 20th Century to the island’s Plantation Era in the 1790’s. The first stop was the Tabby Barn.

20th Century Tabby Barn

This storage barn was built around 1925 by four brothers – Charles, Arthur, Archibald and Reginald Taylor.

They bought this property (then known as Lawrence Plantation) from Mrs Anna Gould Dodge, widow of Christ Church rector Anson Dodge, Jr in 1921.

The brothers farmed and raised free-range cattle and hogs at Lawrence and on properties they leased, including Cannon’s Point and Hampton Point.

From the 1920’s – 1960’s, Taylor Brothers was the largest producer of beef and pork in the area.

The barn was originally used to store corn to feed their livestock.

Tabby Revival

The barn walls are made of tabby, a building material first used on St Simons Island by General Oglethorpe in the late 1730’s to construct Fort Frederica.

When the Taylor brothers built the barn, tabby had not been generally used on the island for about 75 years.

The brothers made tabby in the traditional way.

-

-

-

- Oyster shells were retrieved from prehistoric shell middens and burned to make lime.

- Clean sand came from sand bars in the nearby Hampton River.

- These ingredients were mixed with salt-free water and poured into a bottomless cradle made from long wooden boards held together by wooden pegs.

-

-

After the mixture hardened, the forms and pegs were removed and placed on top of the first pour. The process was repeated until the wall was tall enough.

Lime-based stucco was applied as the last step.

Once we got on the dirt road, we found many side-trails with smaller archeological sites on the way from Taylor’s Fish Camp to the ruins of the big Couper plantation house.

Ruins left from the Couper plantation include slave cabin rubble, the brick chimney of the overseer’s house, and the plantation complex on the Point that includes the main house and a detached kitchen.

The plantation complex was built with tabby taken from Fort Frederica, poured tabby, and bricks.

Cannon Point’s Slave Community

Though the original Charter for the Georgia Colony prohibited slavery, by 1752 the Charter had expired, and the practice took hold in the area.

From the 1790’s until 1861, Cannon’s Point was a cotton plantation wholly dependent on the labor of enslaved Africans.

The main cash crop was Sea Island cotton, a special variety well-suited to the climate and soil of the barrier islands.

The plantation’s slave community of four duplexes housed eight families assigned to work in nearby cotton fields.

Built around 1830, each 40×20′ building had a central dividing wall and a brick chimney which had two fireplaces to provide a hearth for each 20×20′ home.

Each unit had a front and back door, plank floors, and several shuttered windows.

Attic space was used as a sleeping loft.

The families shared a central outdoor well, and each duplex had an outhouse.

Behind the homes they kept vegetable gardens, and most families also raised chickens, pigs, and an occasional cow.

After the Civil War, former slaves returned to Cannon’s Point and lived on the site while working as sharecroppers.

Eventually, the community was abandoned.

Plantation Task System of Labor

Most agricultural plantations used a work process called a “Task System of Labor”.

Under the task system, enslaved workers at Cannon’s Point cultivated 200-300 acres of cotton and 25 acres of food crops.

Each slave was assigned a daily task according to age, gender, and ability.

Cultivation of Sea Island cotton was labor intensive. The season started in late winter with hoeing down the old cotton beds and creating new ones.

Planting began in March, followed by three rounds of thinning to preserve the best plants.

By early September, the cotton bolls had broken open, and the strenuous task of picking began.

A typical day’s work yielded 100 pounds of cotton per worker. Women usually picked more than men.

After ginning to remove seeds, the cotton was sorted, cleaned of debris, and hand packed in hemp bags for shipping. These activities extended into January – and then the cycle started over again.

When daily tasks were completed, men hunted and fished to supplement the family diet. They also made furniture and other household items for personal use and to sell.

After working in the fields, women cooked, did household chores, cared for children, and tended the vegetable gardens and livestock.

Surplus vegetables, meat, and eggs were sold to provide the money for household goods and personal items such as clothing accessories, clay pipes and tobacco.

Overseer’s House Site

An overseer managed the day-to-day operations of a plantation and supervised the work of the enslaved laborers. He also distributed weekly rations to the families.

Often overseers were farmer’s sons who needed the experience and funds to start their own farms.

According to plantation records, the Cannon’s Point overseer earned from $200-400 per year in the 1840’s-1850’s. Turnover was frequent, with personnel changing an average of every 1.5 years.

An Exceptional Dwelling

Usually, an overseer’s house was similar to the 2-room dwelling of a slave family.

In contrast, the Cannon’s Point structure is the size and quality comparable to the owner’s house on a small plantation.

Measuring 36×34′, the 1.5 story frame building stood on clay brick piers and had clapboard siding. Other features:

-

- The home had a wide central hall with two rooms on each side.

- Between each pair of rooms was a brick chimney with a fireplace on either side.

- Interior walls and ceilings were plastered.

- The spacious loft on the second floor provided additional sleeping space.

Artifacts found at the site indicate that the house was probably built during the 1820s.

Remnants of a poured tabby floor and chimney nearby indicate a detached kitchen. The site also had a well and a privy.

A Brief History of Slavery

In recent times when we think of slavery, what comes to mind most often is the enslavement of Africans on the plantations in the American South prior to the Civil War.

But it was 9000 years ago (6800 B.C.) in Sumeria – today’s Iraq – that slavery first appeared in history.

It then spread into Greece and other parts of ancient Mesopotamia, and over time, the rest of the world.

-

-

-

- We know that in the 1700s B.C., the Egyptian pharaohs enslaved the Israelites, as we are told in Exodus Chapter 21.

- Later, the pagan Greeks in ancient Sparta and Athens relied fully on the slave labor of captives. (A famous slave uprising of that time is the story of Spartacus in Sicily.)

- The Ancient East, specifically China and India, didn’t adopt the practice of slavery until much later, as late as the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC.

- In ancient Rome, as many as one in three of the population in Italy (one in five across the empire ) were slaves. This was the foundation of the Roman state and society.

- By the 8th century A.D., African slaves were being sold to Arab households in a Muslim world that, at the time, spanned from Spain to Persia.

- Vikings raided Britain from 800 AD and sold their captives to markets in Istanbul and Islamic Spain.

- By the year 1000 A.D., slavery had become common in England’s agricultural economy. (Slavery gradually disappeared in western European countries, replaced by the serfdom of the feudal manor.)

- In the early Middle Ages the Church condoned slavery – opposing it only when Christians were enslaved by ‘infidels’.

- During the eastward expansion of the Germans in the 10th century so many Slavs were captured that their racial name became the generic term for a ‘slave’.

- During the same period the delivery of slaves to the Black Sea region was an important part of the early economy of Russia.

- The Atlantic slave trade began in 1444 A.D., when Portuguese traders brought the first large number of slaves from Africa to Europe.

- Eighty-two years later (1526), Spanish explorers brought the first African slaves to settlements in what would become the United States

-

-

An Evil of Civilization

For hunter-gatherers, it made no sense to own slaves; since they only kept or hunted enough food to eat at the time, a slave was just another mouth to feed.

But when humans began to live in towns and cities, on large farms, and create things in workshops or factories, there was real benefit to a reliable source of labor that cost no more than the minimum of food and shelter – i.e. slaves.

Slavery made it easier for communities to accomplish physically hard tasks, and increase food production or profit from trade.

Every ancient civilization used slaves, and it was easy to acquire them.

War was the main supplier, and wars were frequent and brutal in early civilizations.

Enemies captured in war were commonly kept by the conquering country as slaves.

Slavery Outlawed

The 1800’s saw a surge of anti-slavery sentiment, and between 1803-1865 most European countries and the US made the slave-trade illegal.

But world slavery did not end with the passage of the 13th Amendment – sadly, many areas in the world continued the use of slavery until very recently.

The last country to abolish slavery was Mauritania in 1981. But they didn’t pass laws to prosecute slaveholders until 2007.

Even today in Mauritania, local rights groups estimate that up to 20% of the population is enslaved, with no possibility of freedom, education or pay.

Modern Slavery

Slavery in the 21st century continues, and generates $150B in annual profits. Some countries still allow the legal use of slaves, others are traded illegally.

In 2019, there were estimated to be 40 million people still trapped in modern forms of slavery, 20% of them children. Most (61%) are used for forced labor in the private sector, and 38% live in forced marriages.

Other forms of modern slavery include indebted servitude, child soldiers, and sex trafficking. Go to the US Department of State site to learn more.

The ruins of the Couper plantation house on Cannon’s Point was the last stop, and turn-around on our hike in the preserve.

To our delight, we found not only the ruins, but a 2-story Observation Tower.

We climbed the stairs for an arial view of the ruins, and a view of the coast.

The Couper Plantation

The namesake and first English owner of the property was Daniel Cannon.

Cannon was awarded a land grant by the Trustees of the Georgia Colony in 1738, but didn’t move to South Carolina from Scotland until 1741.

A carpenter by trade, Cannon worked at Fort Frederica. He lived on Cannon’s Point in a modest one and one-half story cottage he built himself.

John Couper, who immigrated to America from Scotland before the American Revolution, acquired Cannon’s Point in 1793.

With his business partner James Hamilton, Couper helped develop Sea Island cotton as the major cash crop on St Simon’s Island.

Couper also planted citrus trees, Persian dates, sugar cane, grapes, olive trees, and even mulberry trees to use for silk production.

The first large planter to live permanently on St. Simons, Couper often said he left Scotland at sixteen “for the good of his native land” to seek his fortune in America.

He was first an apprentice, and then became a successful merchant. Couper married in 1792, and in 1796, moved his family to St. Simons to live in the same modest house that had been built by Daniel Cannon.

In 1804, the Coupers moved into the handsome mansion that we can see remnants of today.

The ground floor was built of tabby with the wooden upper story-and-a-half painted white with green blinds.

Broad steps led up to a wide piazza that surrounded the second story and provided a magnificent view of the Hampton River and the distant marshes.

You can see this view today from the top of the 2-story Lookout Tower constructed at the plantation house ruins.

The Coupers were gracious hosts, and Cannon’s Point was rarely without visitors.

As a planter, Couper earned the respect of his peers through his experiments with various seeds of sea island cotton that improved its yield.

Couper was community-minded and served as a member of the Georgia legislature and a delegate to the state constitutional convention.

And when need arose for a lighthouse at the southern end of St. Simons, Couper sold the land it stands on to the United States government for just one dollar.

John Couper died in 1850, and his son James Hamilton – one of the Couper’s family of three boys and two girls – acquired the plantation.

At the beginning of the Civil War, St Simons Island planters abandoned their homes and moved inland.

The Union navy controlled the island from 1862 until the end of the Civil War in 1865.

James Hamilton, having suffered a stroke, sold Cannon’s Point to John Griswold of Newport, Rhode Island, a few months before he died in 1866.

William R Shadman of Pennsylvania bought the property in 1877 and grew grains, sugar cane, and sweet potatoes. He also marketed olives and oranges from the Couper groves until a hard freeze killed the trees in 1886.

The house burned in 1890.

Preserve Info

To fully enjoy your visit, be aware that only biking and walking are permitted once your vehicle is parked at Taylor’s Fish Camp.

Also, there is no access to potable water and limited access to restroom facilities.

Location and Directions

The only entrance to the Preserve is off Lawrence Road at Cannon’s Point Drive, a private road that leads to the old Taylor’s Fish Camp on Lawrence Creek.

Sorry, no pets are allowed 🙁

Preserve Entrance Address:

Cannon Point Rd, Saint Simons Island, GA 31522

Directions: Go north on Frederica Road. At the traffic circle on the north end of the island, take Lawrence Rd. Travel about 3 miles and there will be a sign for Cannon’s Point Preserve on the right side of the road.

Follow the directions to the parking lot.

Hours and Fees

OPEN: Saturdays, 9am – 3pm; Sundays and Mondays, 9am – 3pm

For more details, see the preserve’s website.

There are no entrance fees to enjoy the Preserve.

View of the Lighthouse from the St Simon’s pier.

Other Nearby Attractions

While you’re in St. Simon’s, be sure to stop by and see the lighthouse! We didn’t go inside the Museum (it was closed when we walked by), but it’s worth a visit.

St Simon’s Lighthouse

St. Simons Island Lighthouse was originally built in 1810 by James Gould of Massachusetts, the first lighthouse keeper.

The Lighthouse still serves as an active aid to navigation for ships entering St. Simons Sound, casting its beam as far as 23 miles to sea every 60 seconds.

The original lighthouse was destroyed by Confederate forces in 1861 to prevent the beacon’s use by Federal troops during the Civil War.

The current structure is one of only five surviving light towers in Georgia.

Visitors may climb the 129 steps to the top to experience spectacular views of the coast.

The light keeper’s residence is a two-story Victorian brick structure that was the home of lighthouse keepers from 1872 until the 1950s. Today it houses the Lighthouse Museum.

For more information about hours, admission rates and group access, click here.

Jekyll Island

Jekyll Island, the southernmost island of the Golden Isles, is a popular destination coastal Georgia visitors.

It’s just a short drive from St Simon’s, and we were fortunate to have one (mostly) sunny afternoon there during our rainy February visit.

We just enjoyed a great walk on the beach (the 5,500-acre island features 10 miles of shoreline) but in season the island hosts a variety of events, family-friendly activities, and attractions.

Jekyll Island was part of the original 1733 Georgia Colony. The island was named for Sir Joseph Jekyll, one of the venture’s financial supporters.

Jekyll Island was part of the original 1733 Georgia Colony. The island was named for Sir Joseph Jekyll, one of the venture’s financial supporters.

In 1886, following the Civil War, Jekyll Island was purchased by a group of wealthy families as a private retreat.

By 1900, The Jekyll Island Club membership included the Rockefellers, Morgans, Cranes, and Goulds and represented over one-sixth of the world’s wealth.

The Club closed in 1942 and Jekyll Island was purchased by the State of Georgia in 1947.

Have a great trip to Cannon’s Point Preserve on St Simon’s Island! If you have any questions or comments, drop me a note and I’ll get back to you as quickly as I can.

If you’re looking for more ideas for hiking with small children – without driving to the Coast – try Raven Rock State Park .

Thanks for stopping by – see you next time! LJ

To Get New Idratherwalk Posts

sent directly to your inbox (how convenient!) Click this Button

If you enjoyed this post, please share it:

LJ has spent much of her free time as a single Mom – and now as an empty-nester – hiking in the US and around the world. She shares lessons learned from adventures both local and in exotic locations, and tips on how to be active with asthma, plus travel, gear, and hike planning advice for parents hiking with kids and beginners of all ages. Read more on the About page.